Proposal: Advance Directives for our digital legacies

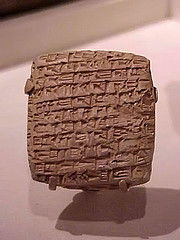

Ten years from now, which is most likely to still be around, your last email or this one by some ancient Assyrian businessman?

Photo by mharrsch / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

One thing I can tell you is that when the photographer who took this image stops paying for their Flickr account, this photo is likely to disappear, and all sites that hotlinked to it using Flickr’s “embed” feature, will lose the use of it.

As more of our lives are conducted on the web, more of our memories and creative work – whether social, artistic, or technical – are likely to be online. Years of online communications, discussions, virtual property, artwork, music, applications, and even the metadata we add to social networks are accreting into mountains of information in the cloud and on rapidly aging media around all of our houses.

What happens to your accounts when you die?

Despite all the digital ink spilled cautioning us not to leave embarrassing digital remnants to haunt us for the rest of our lives, “the rest of our lives” are really not that long, on a cultural scale. Our virtual creations are both fragile and ephemeral, in ways that are historically unique. Never has so much human output been so easily erased, worldwide. This has implications for future generations’ ability to benefit from what we have created and to understand the past.

Take a few moments to mentally inventory the sites and devices on which you’ve texted, written, chatted, amassed virtual property, twittered, blogged, and uploaded video. What will happen to it all when you die? Are there any items you would prefer to remain behind once you are gone? Are there items that should not remain? Is there any way at all to ensure your wishes are met?

If you are over 20, your family probably has a few boxes of photos stashed away somewhere from before film cameras faded away, including some inherited from grandparents and great-grandparents. In contrast, your own descendants could very likely not inherit any of your photos unless you plan carefully for their survival in a way your parents never had to. And the same with any of your other digital works.

Will enough of our personal communications survive so that future historians can trace events? Most of us aren’t politicians, diplomats or presidents, so we view our informal interactions as disposable, but it’s hard to say what will be considered “important” in 50 years time. With more adults streaming into services like Facebook, the combination of interactions becomes the content, and that will be very hard for a historian to reconstruct.

It’s a complex problem that will become more critical over the next few years as more netizens pass on, leaving behind closed accounts and vanished data on many different services. Flickr is a good example: assuming you have a paid account, once you stop paying, most of your photos willl be hidden from view. You may have your images backed up at home, but items that were formerly available to the public will certainly be lost to public view, and any metadata that was added to the images will certainly be lost. SImilarly with YouTube, Photobucket, Google Video, MobileMe, AOL, etc.

What happens to your content when companies or their products and services die?

When companies go out of business or decide a product has outlived its value, vast oceans of content are likely to be lost as well. Sometimes that’s not an obvious problem – as witness the recent demise of Geocities, or the removal by AOL of years of message boards – but it could turn out to be.

Unlike real artifacts that last until someone throws them out or destroys them, digital items can be destroyed wholesale and worldwide in an instant. Supposing there were a natural disaster, or a war, it might destroy all the artwork in a city, or even several cities, but not all the artwork by a certain artist all over the world – or all the photos of 10 million people from all over the world. Now, it is entirely possible that this could happen.

With digital property, we could probably learn from the aerospace industry’s insistence on triple redundancy. Not just stored in the cloud, not just stored at home, but also in a third place, under a different financial arrangement.

Right now, some of the web is supposedly cached by the Internet Archive, but there is little consistency, and usually, communities and data exist only as long as there is money paying for them to exist. When that money stops flowing, the data disappears. There is no law of nature saying there must be an archived backup showing how things used to look.

Cases in point:

- Arxiv, a huge open-access archive of scientific articles from all over the world, is run by Cornell University. They recently requested funding from other institutions because Cornell can’t afford to support what Arxiv on the scale that is now necessary.

- An artist I know died a few years back, and her husband kept paying the site bill as a memorial – but once he discontinues the account, the images of her work will vanish. Other than on that site, there is no good compendium of her artwork. Not every artist is memorialized in museums – many use the web as their museum.

- A large library of information on Javascript, created by Netscape disappeared from view for a while until someone (Mozilla) was found to host it.

- The UseNet groups dating back to 1981 nearly disappeared about 9 years ago when Deja News shut down for lack of funds. Google acquired the archives, and incorporated them into Google Groups.

- A software developer who helped create the technical standards used everyday in online learning systems all over the world died a couple of years ago, and his site vanished along with all the resources it contained. It’s been rescued, at least temporarily, but there are probably many pages of software history which have not been.

Permanence and Privacy

If you are concerned about maintaining data permanently (greater than a decade), you may want to consider these issues:

- Items and data that exist in paid accounts will vanish when those fees cease to be paid.

- Items and data that exist in private companies’ servers may not last past the bankruptcy or buyout of that company.

- Any item that changes, or is deleted can not be assumed to be cached by any service.

- Any item on any server that is not encrypted and even some items that are cannot be assumed to be private, especially if the company is sold or transferred.

- Files and data that are moved or downloaded from a social networking service or copied to another type of service for backup may lose metadata that is as important to users as the item itself.

- Items you maintain on home-based media may become incompatible or unreadable in a very few years time.

The issues are so large that I suspect we will probably need to invent new legal instruments as well as new technical infrastructure to deal with the changing realities.

Wills or Advance Directives for data

Advance directives are legal documents that allow you to convey your decisions about end-of-life care ahead of time. Perhaps we should develop something similar to convey our wishes about our data. Artists may want to endow a permanent gallery account for their work, particularly if it is digital in nature. Families may want to set up some sort of permanent online archive for their photos that is not dependent on an individual’s account remaining active. People that are involved in activities of historical interest may decide to will their email or Facebook (don’t laugh!) accounts to a library or policy institute, to be opened 50 years after their death. People with photo accounts may want to allow all of their photos to go public 50 years after they die – assuming the data and some form of the web are still extant.

Children growing up now will soon have decades of text messages or other communications with their parents – starting from toddler age in some cases – and they may have to request phone records to see them later in life. Who owns all of that conversation? The phone companies?

Sounds like a good case for a legal document, doesn’t it? We are only beginning to discover the new realities of durability, privacy, security, intellectual property, and the rights of the individual vs. the rights of society.